Sufyanu, a 3-year-old boy from Sokoto, Nigeria state standing in the courtyard of the Noma Hospital in Sokoto. October 2016.

© Claire Jeantet & Fabrice Catérini/Inediz

Noma: A hidden childhood disease

Improving Health

Sharing Love

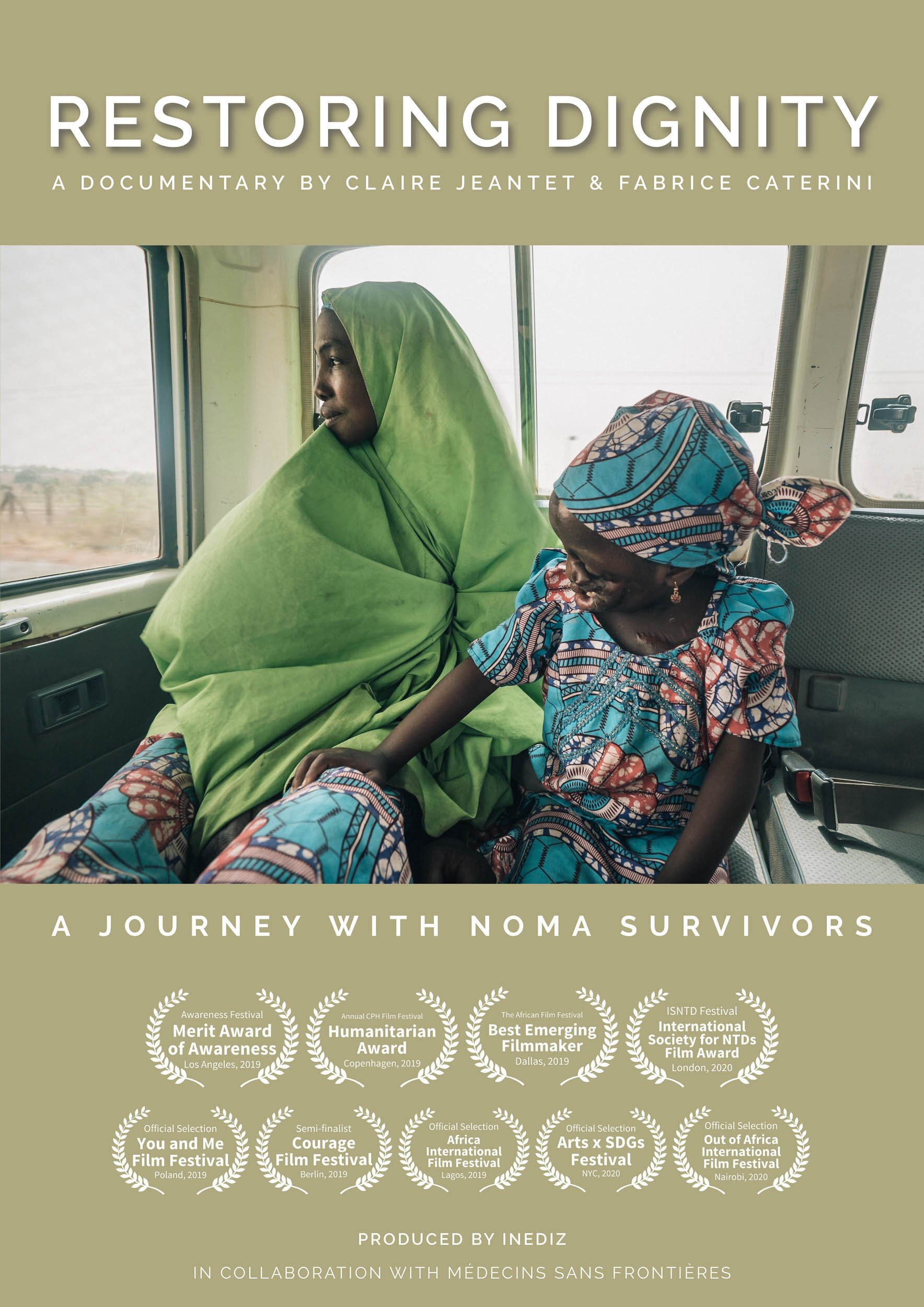

Restoring Dignity

MEET THE TEAM

Click on the images to find out more about our 2025-2026 team members!

Camryn Rohringer

Sol Park

Meghan Paleolog

Isabella Rossini

Hongyan (Yan) Liu

Chukwuma Benedict

Ifeanyichukwu Ezeliorah

Sherry Wang

Kaitlyn Jacob

Claire Jeantet

Dr. Rosenbloom

Hellen Huang

Ocarina Zheng

Team Alumni

Dr. Joel Rosenbloom DDS

Staff Dentist, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH)

Assistant Professor Teaching Stream, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto

Adjunct Assistant Professor, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

Member/Co-Founder, NAG/Noma Action Group

“I wrote this memoir to capture my experiences living in Mozambique …

and working as a dentist during the mid to late 1980s when Mozambique was at a turning point in its history. The Revolution of 1975 was in peril. South Africa’s intolerance of Black majority rule in the region gave rise to its war of destabilization in Mozambique, rolling back many gains since its independence from Portugal. Their proxy was Renamo, or the ‘Resistência Nacional de Moçambique’.

In its first decade, the Mozambican Revolution was one of the most successful societal transformations on the globe, working towards the creation of a just and equitable society. It was designed to provide widespread health and education services for the population, and land redistribution to empower rural communities. Mozambique became a beacon for International Socialists and left leaning academics, attracting dedicated professionals and political refugees from around the world.

I made the decision to work in Mozambique as a government dental officer to support Frelimo and its revolution and the rebuilding of a new oral health system. Frelimo, or the ‘Frente de Libertação de Moçambique’, is the name of the political party that fought the armed struggle and became the government at independence. When I arrived, the war was becoming steadily more brutal and bloodier, it was hard to imagine how this would turn out. The massacres of almost 500 people by Renamo in the southern Mozambican towns of Homoine and Manjacaze were watershed moments in the war.

During my two plus years in Mozambique, I saw the transition from a state trying to distribute services and resources to all people amidst the challenges of external aggression, to a country brought to its knees by war. The revolution was crumbling, that much was clear, but whether it would survive the intervention by South Africa was not.

The next fundamental shift was the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) imposed on Mozambique by the World Bank and the IMF (International Monetary Fund). It was these agreements that would ultimately move the country towards ending the war, but they marked the first stage of failure of Frelimo’s Marxist project. It was also these agreements that led to the largest influx of foreigners and foreign investment into an extremely poor country in the shortest amount of time on record. Living through and watching this monumental change unfold was a unique opportunity to see yet another type of societal transformation and to see how these policies trickled down to affect the lives of Mozambicans.

I was interested in portraying life during the war, writing about the uniqueness of Mozambique: from my daily struggles, to the broader political context, to my role as a dentist. I brought this period to life through stories, vignettes, photographs, sketches and ephemera. More importantly, I wanted to document how this period affected me and the people around me: patients in the hospital, Mozambican friends and ‘cooperantes’ (development workers) through my unique window as a Frelimo dentist.

The famous French New Wave filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard lived in Mozambique in 1976-77. He described it as ‘the country most unaffected by images on the planet’ and he wanted to explore the impact of images on an emerging society. It was this rawness that made Mozambique so unusual and so interesting to delve into.

I wanted to tell stories about living in a country where deprivation was the norm and everything had to be considered through the lens of the war. I learned to expect the unexpected, yet was repeatedly inspired by the resilience and kindness of Mozambicans. I found optimism where I least expected it and made many meaningful friendships with Mozambicans and ‘cooperantes’.

I also saw deep pain and sadness. Seeing a child suffering from noma was life-altering. Noma is a form of orofacial gangrene affecting young children living in poverty. The famous Swiss Explorer, Psychiatrist and Environmentalist, Dr. Bertrand Piccard wrote about noma: “When we first hear its name, we do not know what it is. When we hear it described we cannot believe what we hear. And when we see it with our own eyes, we will never be the same again

I could have written this in 1987 in the Central Hospital of Beira when I saw a child with noma. I already knew about noma, even expected to see it, but I could not imagine the devastating emotional impact of this experience."

© Jeff Comber

Claire Jeantet

Restoring Dignity Co-film maker

Noma Campaign Manager at Médecins Sans Frontières